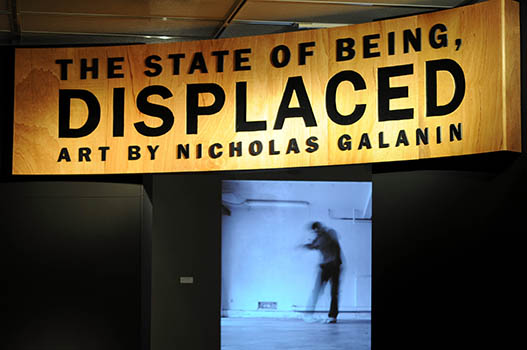

Nick Galanin: The State of Being, Displaced

at the Alaska State Museum

May 17, 2013 to October 12, 2013

“CULTURE

CANNOT

BE CONTAINED

AS IT UNFOLDS.”

“My art enters this stream at many different points, looking backwards, looking forwards, generating its own sound and motion. I am inspired by generations of Tlingit creativity and contribute to this wealthy conversation through active curiosity. There is no room in this exploration for the tired prescriptions of the “Indian Art World” and its institutions. Through creating I assert my freedom.

Concepts drive my medium. I draw upon a wide range of indigenous technologies and global materials when exploring an idea. Adaptation and resistance, lies and exaggeration, dreams, memories and poetic views of daily life--these themes recur in my work--taking form through sound, texture, and image. Inert objects spring back to life; kitsch is reclaimed as cultural renewal; dancers merge ritual and rap.

I am most comfortable not knowing what form my next idea will take; a boundless creative path of concept-based motion.”

Nicholas Galanin

2013

Courtesy of the Alaska State Museum

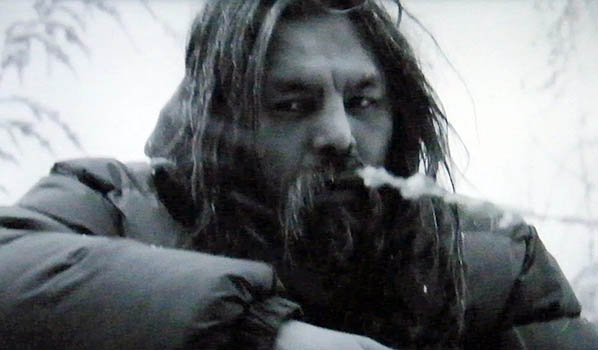

Photographs by Sara Boesser

|

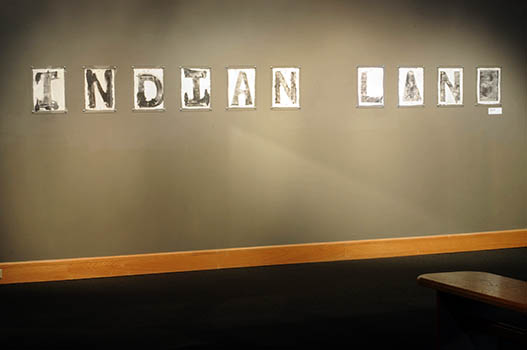

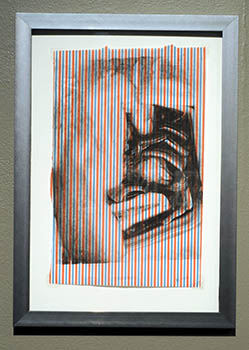

INDIAN LAND

Monotype

2013

Born in Sitka, Alaska, Nicholas Galanin has struck an intriguing balance between his origins and the course of his practice. Having trained extensively in ‘traditional’ as well as ‘contemporary’ approaches to art, he pursues them both in parallel paths. His stunning bodies of work simultaneously preserve his culture and explore new perceptual territory.

Galanin studied at the London Guildhall University, where he received a Bachelor’s of Fine Arts with honors in Jewelry Design and Silversmithing and at Massey University in New Zealand earning a Master’s degree in Indigenous Visual Arts.

Valuing his culture as highly as his individuality, Galanin has created an unusual path for himself. He deftly navigates “the politics of cultural representation” as he balances both ends of the aesthetic spectrum.

With a fiercely independent spirit, Galanin has found the best of both worlds and has given them back to his audience in stunning form.

|

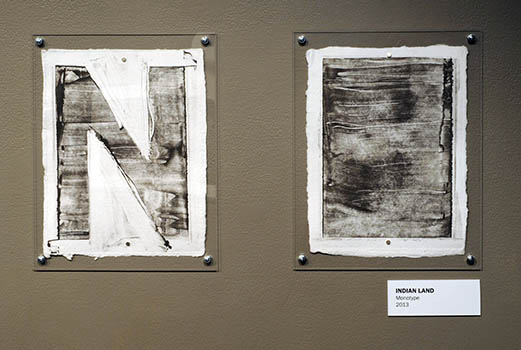

Detail from

INDIAN LAND

Monotype

2013

There are 10 monotype prints in this series. This detail shows the last two.

Every monotype is unique. Monotype prints are made by spreading ink on a smooth surface like Plexiglas, removing and working the ink in place and striking one print from the resulting composition. The results combine the spontaneity of a drawing with the enduring qualities of a print.

|

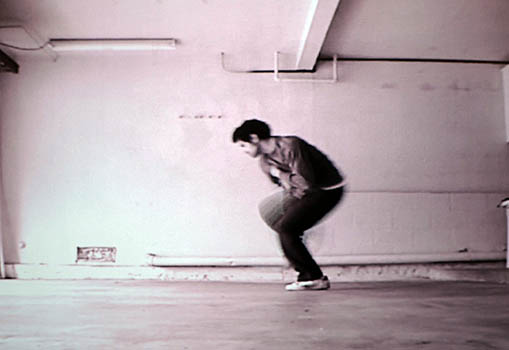

Tsu Héidei Shugaxtutaan

Video

performance by David Elsewhere

2006

The figure dances to the traditional Tlingit entrance song of the same name performed by a solo male voice accompanied by a frame drum.

|

Tsu Héidei Shugaxtutaan

Video

performance by David Elsewhere

2006

|

Tsu Héidei Shugaxtutaan

Video

performance by David Elsewhere

2006

|

Tsu Héidei Shugaxtutaan

Video

performance by David Elsewhere

2006

|

Tsu Héidei Shugaxtutaan

Video

performance by David Elsewhere

2006

|

Untitled

Monotype

2013

|

The State of Being, Displaced

C-print

2013

|

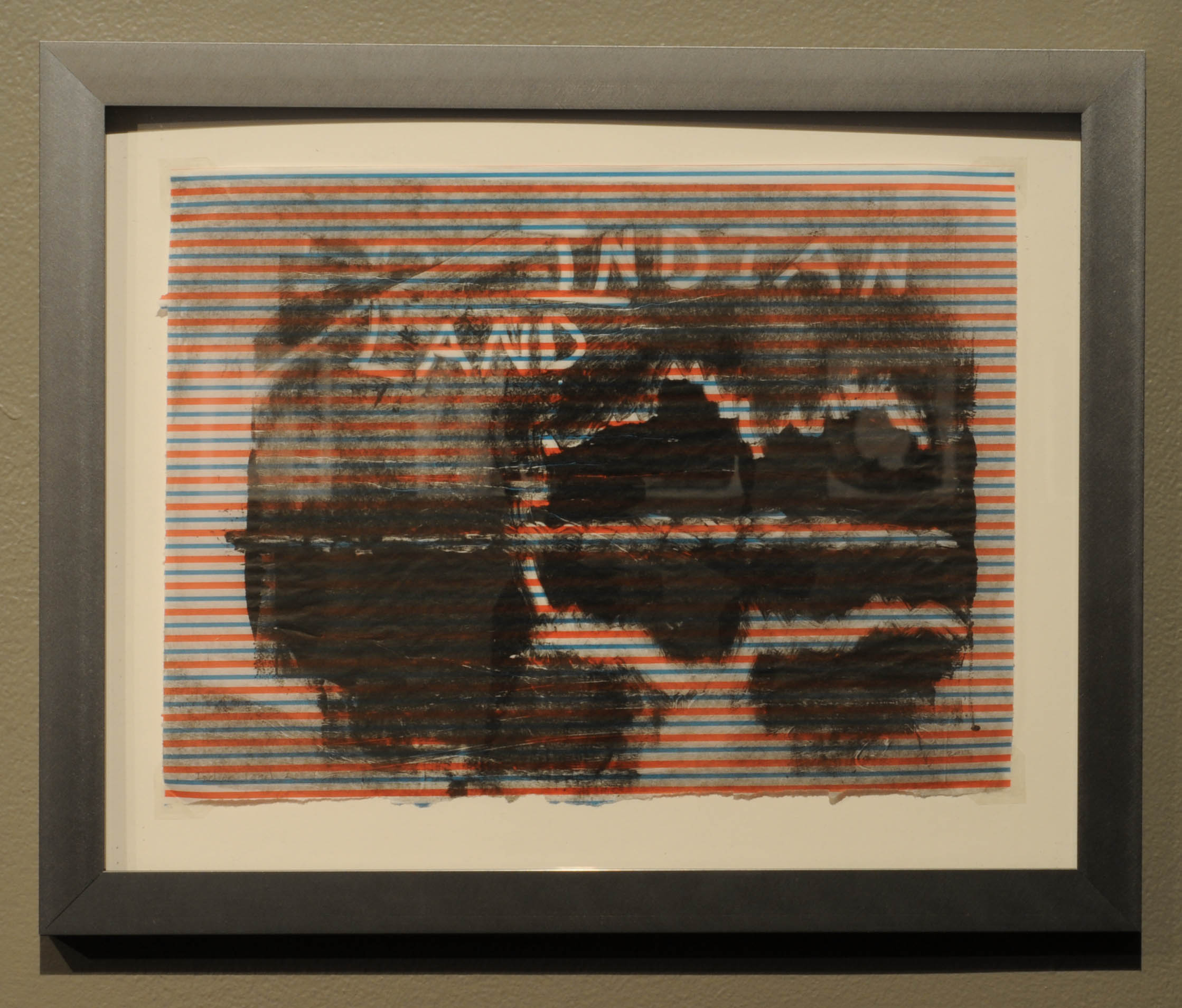

Indian Land

Monotype

2013

|

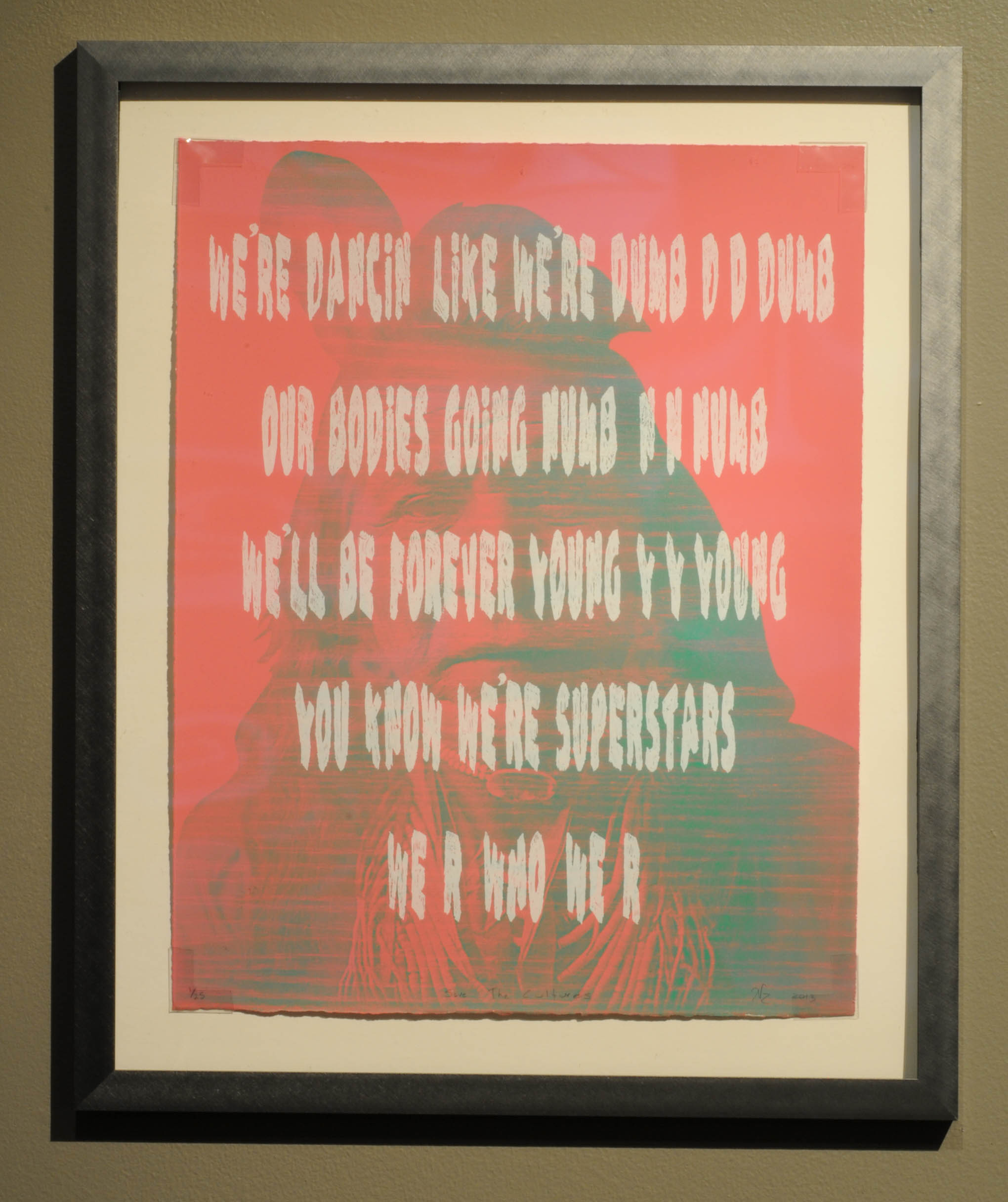

Save The Cultures

Silk Screen

2013

|

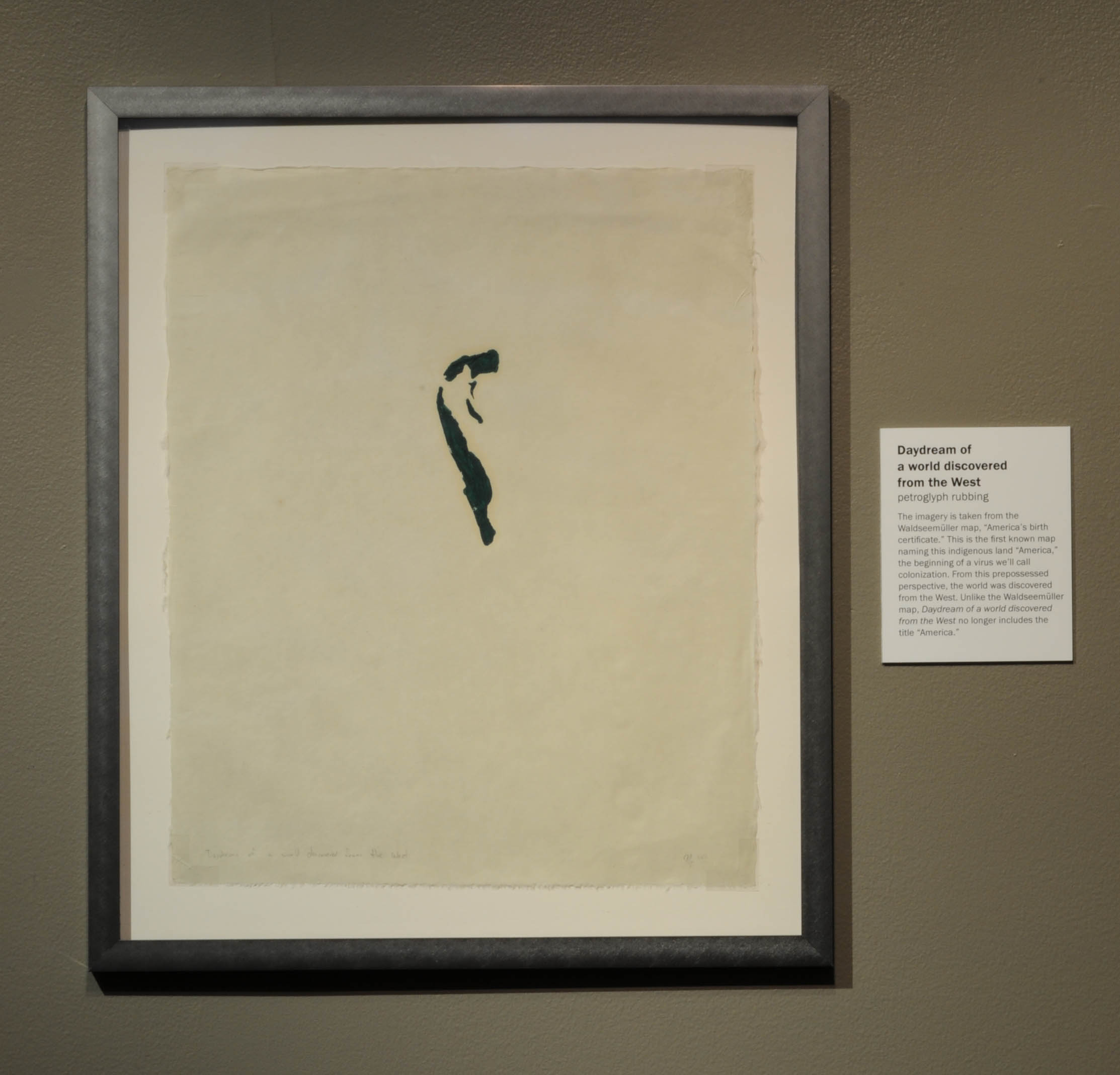

Daydream of

a world discovered

from the West

petroglyph rubbing

The imagery is taken from the Waldseemüller map, “America’s birth certificate.” This is the first known map naming this indigenous land “America,” the beginning of a virus we’ll call colonization. From this prepossessed perspective, the world was discovered from the West. Unlike the Waldseemüller map, Daydream of a world discovered from the West no longer includes the title “America.”

In other venues, Mr. Galanin has reproduced this image as a petroglyph in the floor of the gallery. People were invited to look around and “discover” it for themselves.

|

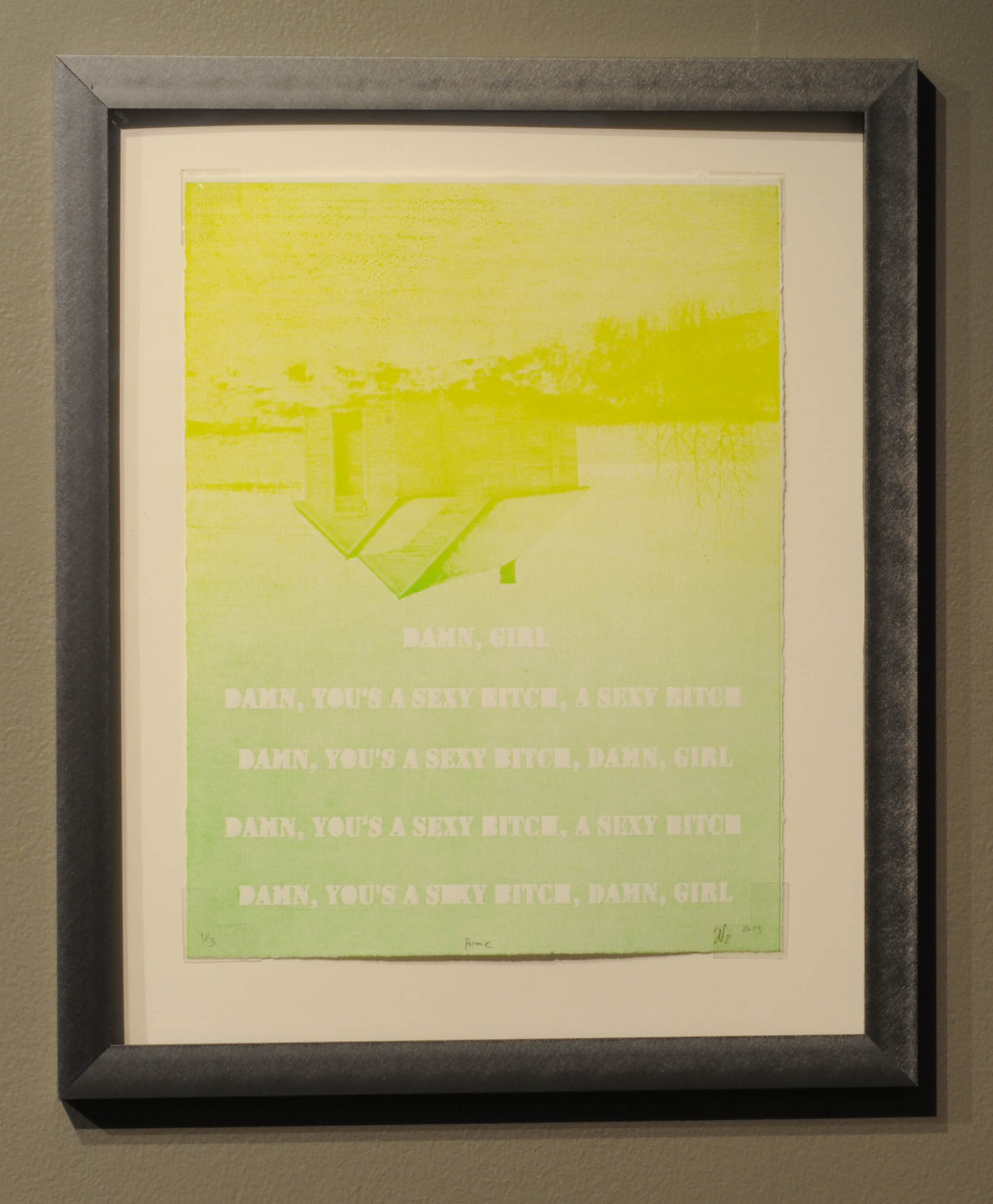

Home

Silk Screen

2013

|

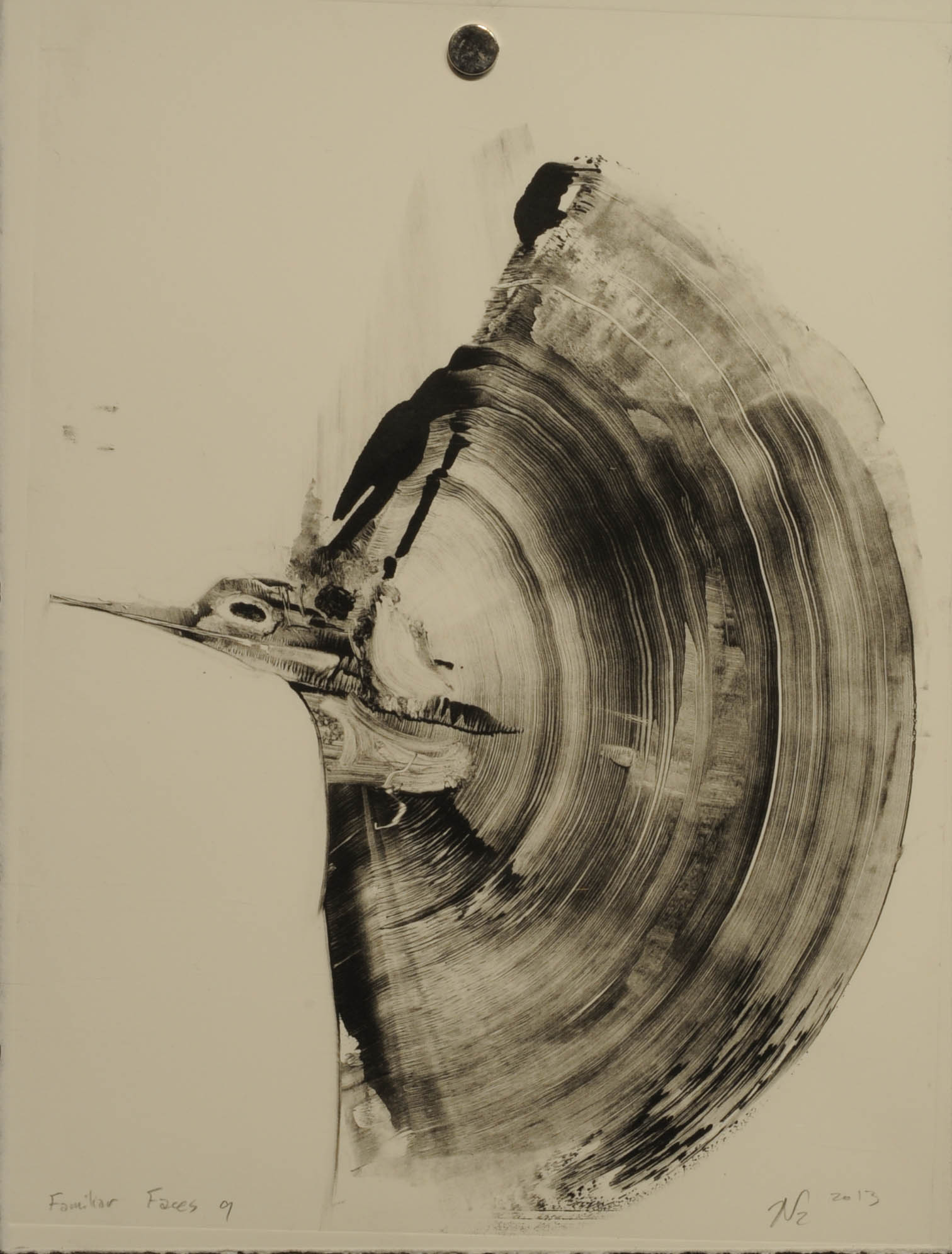

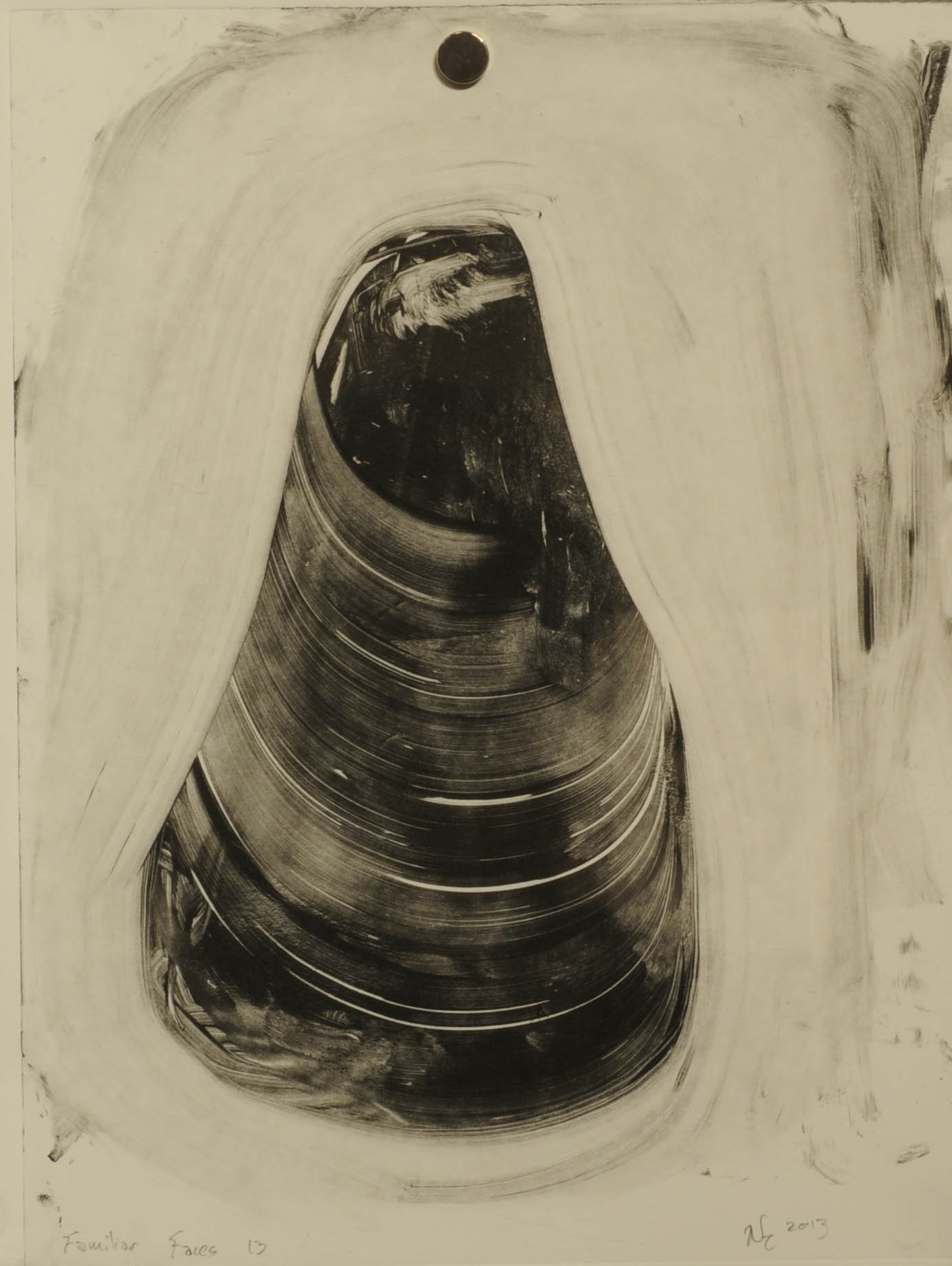

Familiar Faces

Gallery wall showing part of a series of 13 monotype prints of abstracted formline design.

|

Familiar Faces 1

Monotype

2013

|

Familiar Faces 6

Monotype

2013

|

Familiar Faces 7

Monotype

2013

|

Familiar Faces 9

Monotype

2013

|

Familiar Faces 13

Monotype

2013

|

Tsu Héidei Shugaxtutaan II

Video

performance by Dan Littlefield

2006

The figure, in a dance robe and wooden mask, dances to a contemporary piece of electronic music.

|

Tsu Héidei Shugaxtutaan II

Video

performance by Dan Littlefield

2006

|

Tsu Héidei Shugaxtutaan II

Video

performance by Dan Littlefield

2006

|

Things Are Looking Native,

Native’s Looking Whiter

Giclée

2012

|

Indian Petroglyph

16” carved stone petroglyph

C-print

2010

|

Get Comfortable

C-print

2012

|

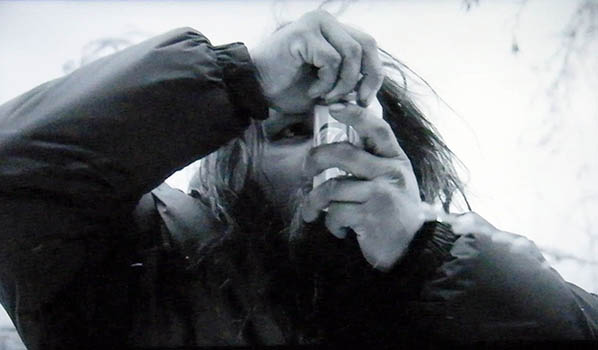

Is This Your Medicine? Man

Video

2012

The voice-over for this video is composed of questions (in English with Tlingit translations) relating to medical care. Questions include:

“Are you sick?”

“Is this your medicine?”

“Is your medicine always running out?”

|

Is This Your Medicine? Man

Video

2012

|

Is This Your Medicine? Man

Video

2012

|

The North Gallery, Alaska State Museum, where Mr. Galanin’s exhibit is displayed.

|

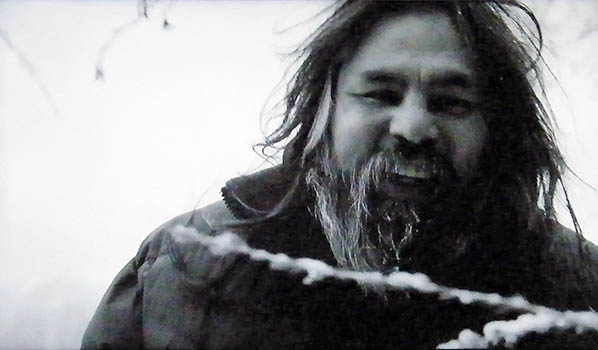

Untitled

Masks at Sheldon Jackson Museum

C-print

2012

|

Untitled

Masks at Sheldon Jackson Museum

C-print

2012

|

Untitled

Masks at Sheldon Jackson Museum

C-print

2012

|

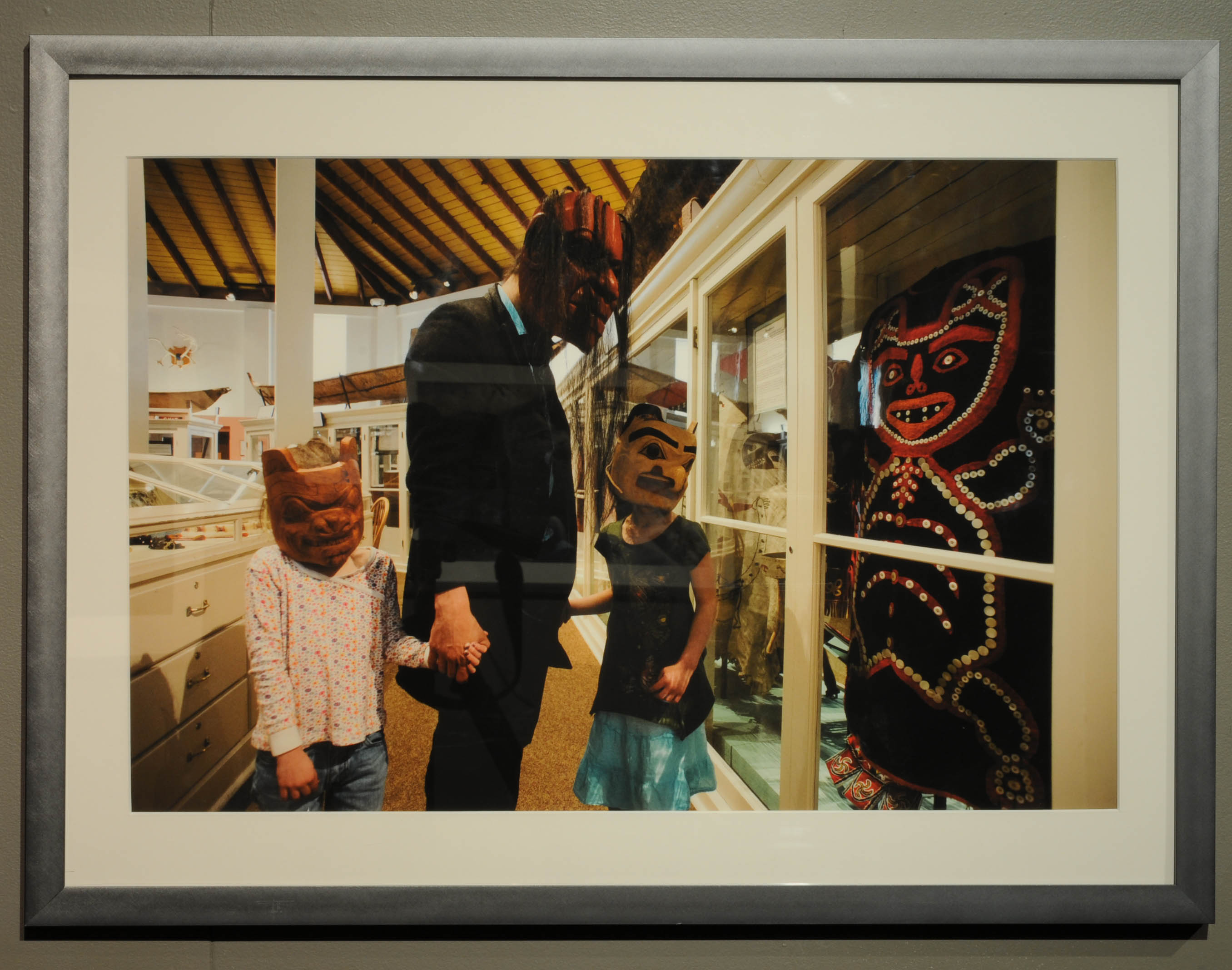

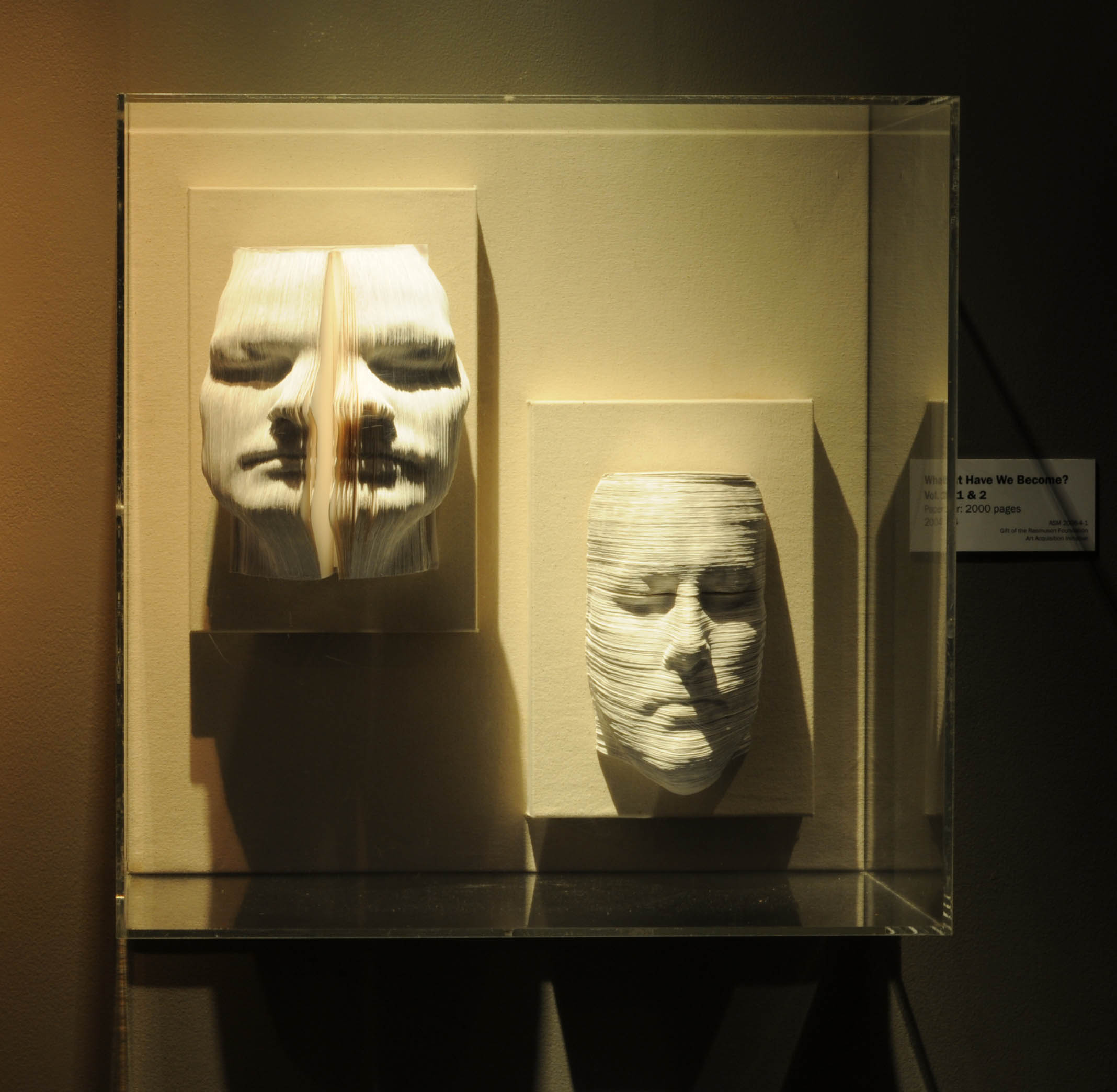

What Have We Become? Vol. 1 & 2

Paper: 2000 pages

2004

ASM 2006-4-1

Gift of the Rasmuson Foundation Art Acquisition Initiative

“As a contemporary Tlingit artist, I find the history so rich it can overpower personal growth as an individual in the art world today. My culture’s art form is distinct and highly developed; one can spend a lifetime within it. In the current Native art world the social scene filters through work defining what is acceptable for the label “Tlingit” or “Native art.” The local art form becomes reactionary to the rest of the art world. Working within or conservatively changing customary forms, artists introduce new mediums often offered through technological change. When a piece of work is missing the visual language used by the Tlingit culture, elders struggle to see themselves in it; this becomes problematic when one tries to define the work as Tlingit art.

The What Have We Become? series confronts the notion of conservative Native art. The concept is pulled from my experience as a contemporary Native artist working in the present day. In the past, Tlingit Culture had preserved history orally through storytelling and visual art. To learn more about my cultures’ history, I have found myself reading scholarly books often written from a foreign perspective. Though this new medium is important in preservation of a culture, it raises questions of identity. As an indigenous artist, I hope to assist in breaking social barriers such as the romantic notion of what native art work should be, as this can hinder the creative license.”

- Nicholas Galanin

These pieces were paired with a video Mr. Galanin made in 2006 entitled Who We Are. The video shows images from “Pacific Northwest Native American Art in Museums and Private Collections: The Bill Holm and Robin K. Wright Slide Collections” (originally published by the Burke Museum, University of Washington, Seattle). The slides are shown rapidly in a continuous loop. The images flash by at a rate of about 5 per second.

The combination of cultural artifacts objectified by their place in a museum and faces emerging from “text books” points out the disconnect often experienced by contemporary artists and lay people trying to learn about a culture in nontraditional ways.

|

Killerwhale Bracelet

Silver

2007

ASM 2007-18-1

Gift of the Rasmuson Foundation Art Acquisition Initiative

|